Shoulder Impingement and Rotator Cuff Problems

Shoulder impingement and rotator cuff problems are familiar sources of shoulder pain. Inflammation and tearing of the rotator cuff are more common with increased age. Treatment options range from medications and rehabilitation to surgery.

Your physician will evaluate multiple factors, such as your age, overall health status, activity level, severity, duration of symptoms, and the degree of damage to the rotator cuff to determine which treatment is the best for you.

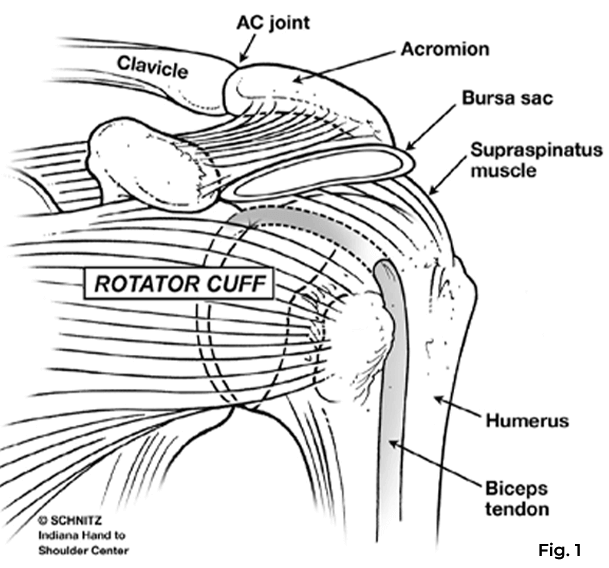

Anatomy

The shoulder is a ball (humeral head) and socket (glenoid) joint surrounded by the rotator cuff muscles and tendons (the cords which connect muscle to bone), which function to stabilize your shoulder joint as you lift your arm overhead.

A rotator cuff is a group of four muscles, but the supraspinatus muscle is the most frequently involved in tendinitis and tears. The upper part of the shoulder blade (acromion) and the collar bone (clavicle) join at the acromioclavicular (AC) joint to form a roof over the rotator cuff tendons. A bursa sac between the rotator cuff and the acromion provides a gliding surface between these two structures. (Fig. 1)

What Is Shoulder Impingement Syndrome?

As one ages, the rotator cuff tendons can gradually deteriorate. These tendons can become inflamed, causing shoulder pain (called rotator cuff tendinitis or shoulder impingement syndrome). The bursa sac usually becomes inflamed along with the rotator cuff tendons (bursitis).

The pain is typically localized to the shoulder or outside the upper arm. It is generally worse with overhead activities or positioning the arm behind the back and often wakes you from sleep. If the pain persists for an extended period, limiting the shoulder use, the joint may stiffen. This is commonly referred to as a frozen shoulder.

What Are the Causes?

There are many causes of rotator cuff tendinitis and bursitis. One common cause is excessive shoulder use, especially in an overhead position. These activities cause rubbing (impingement) of the rotator cuff tendons and bursa sac under the acromion and AC joint.

Anything that causes narrowing of the space over the rotator cuff, such as spurs on the undersurface of the acromion or clavicle or weakness of the shoulder muscles, will predispose the shoulder to rotator cuff tendinitis and bursitis.

Shoulder Impingement Syndrome Treatments

Your physician may decide to obtain X-rays or an MRI to look for spurs, arthritis, or a tear of the rotator cuff tendons. Treatment usually involves rest and avoidance of activities that cause continued irritation.

Medications and injections may be used to reduce pain. If stiffness develops, a home stretching exercise program will be initiated. A specialist may prescribe organizational therapy to reduce pain and restore flexibility.

If shoulder pain persists despite non-operative treatment, your physician may recommend several options. Occasionally, stretching the stiff shoulder under anesthesia helps restore mobility and decrease pain. If your shoulder motion is maintained or corrected with exercises, but your pain persists, your physician may recommend surgery for shoulder impingement.

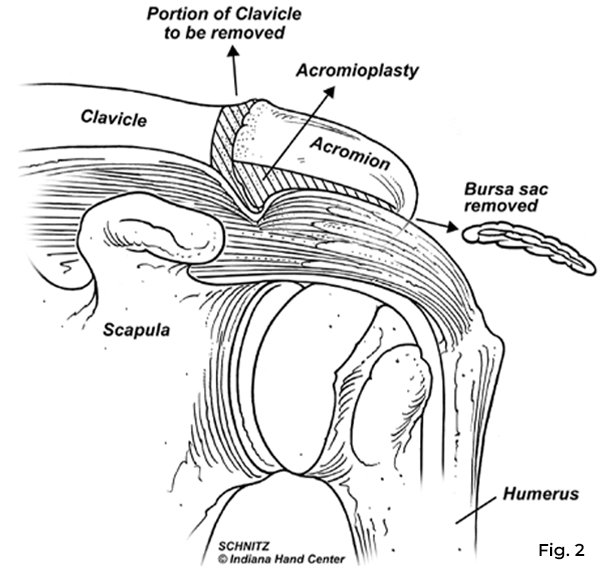

Tendinitis Treatments

To relieve the tendinitis, the space through which the rotator cuff moves is opened, removing any spurs from the undersurface of the acromion (acromioplasty) and removing the thickened bursa. If there is arthritis and spurring of the AC joint, a surgeon may also remove a small section at the end of the collarbone. (Fig 2)

Your physician may choose to perform this procedure through an open incision or a smaller incision with a tiny camera called an arthroscope. The primary advantage of the arthroscopic procedure for treating shoulder impingement is that it is less invasive, allowing for a more aggressive rehabilitation program with a potentially earlier return to full activity.

The surgery is performed under a general anesthetic (you must be put to sleep), along with an anesthetic block to numb the arm.

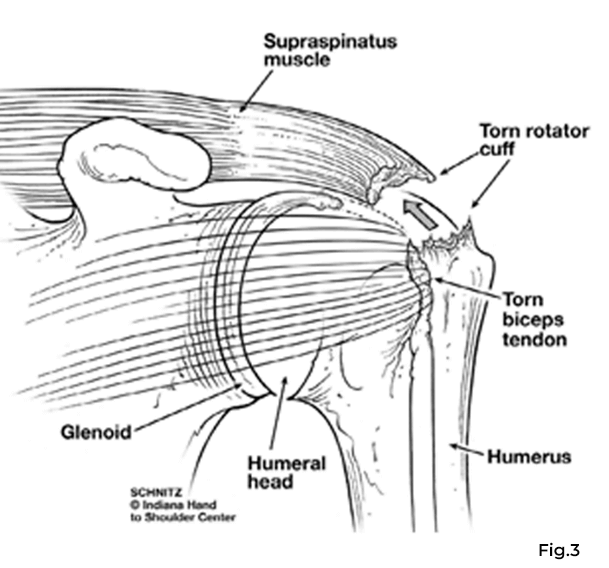

Rotator Cuff Tears

Rotator cuff tendons can tear, usually at the attachment site to the bone. Most tears involve the supraspinatus tendon, but other tendons may also be affected. (Fig. 3)

Most torn tendons start by fraying and weakening secondary to age or repeated grinding of the tendons on the acromion or AC joint. This can lead to a partial tear.

As the fraying progresses, the weakened tendon can tear completely, often while lifting a heavy object. Tears can occasionally occur through a previously normal tendon due to a violent fall or an episode of very heavy lifting.

Symptoms of a rotator cuff tear are very similar to shoulder impingement syndrome, with pain at night, weakness (especially overhead), and a grinding sensation in the shoulder. Your physician might order X-rays or an MRI to assess the rotator cuff.

Rotator Cuff Tear Treatments

Since rotator cuff tears tend to enlarge with time and can’t heal without surgery, surgical repair is usually recommended for most active patients with complete tears. This is especially true for patients with longstanding symptoms, large tears, significant weakness, or an acute injury.

A shoulder specialist may recommend non-operative treatment for small partial tears or in patients with small complete tears or those not healthy enough to undergo surgery. Non-surgical treatment options include rest, activity modification, therapy to restore motion and strength, and medications or steroid injections.

If Surgery Is Necessary

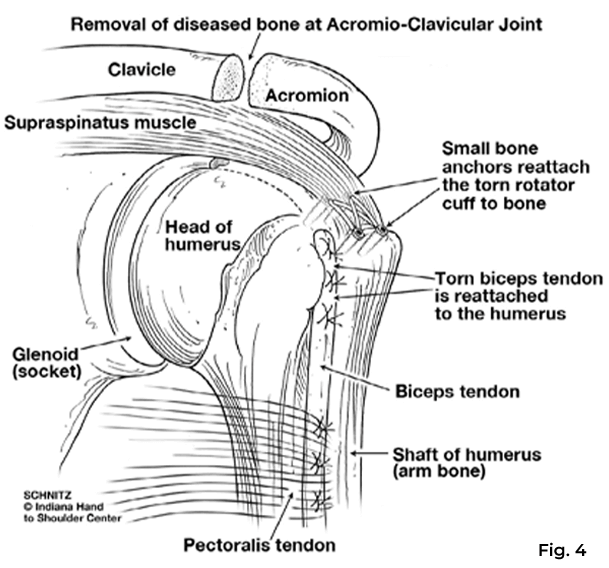

Surgery to repair a torn rotator cuff tendon is done under general anesthesia and an anesthetic block to numb the arm. Surgery often involves reattaching the tendon with sutures attached to anchors placed into the bone.

Your surgeon may perform an acromioplasty, partial clavicle resection, or other soft tissue procedure in addition to the rotator cuff repair. (Fig. 4)

These may be done arthroscopically through a traditional open incision or a mini-open incision. All three repair methods result in the same degree of pain relief, strength improvement, and overall satisfaction.

Post-Operative Rehabilitation

After surgery, therapy progresses in stages. At first, the repair needs to be protected for four to eight weeks while the tendons heal. You will wear a sling and do very gentle exercises during this period.

After four to eight weeks, your sling will be discontinued, and you will begin to move your arm on your own. As the tendon repair gets stronger (eight to 12 weeks), you will start strengthening exercises. Although pain relief is achieved in four to five months, your full return of strength and motion may take up to nine months to a year.

No part of this work may be reproduced without written permission from the Indiana Hand to Shoulder Center.

Disclaimer: The materials on this website have been prepared for informational purposes only and do not constitute advice. You should not act or rely upon any medical information on this website without a physician’s advice. The information contained within this website is not intended to serve as a substitution for a thorough examination from a qualified healthcare provider. The display of this information is not intended to create a health care provider-patient relationship between the Indiana Hand to Shoulder Center and you.

Shoulder Impingement Patient Handout